We’ve seen them before. Some articles seem to be written by people whose primary fixation in life is “me, me, me.” Everything they experience is viewed through the same me-colored lens, which, with its haze of scratches and fingerprints from excessive vanity, makes the most trifling of life’s events seem ageless, even grand.

This is one of those articles.

Hold on, though. There’s more to it than that. This is the story of a personal journey through the world of music that begins humbly and ends just as humbly as it started. The fact that your reporter (should I say “moi”?) has experienced it at all is amazing enough, for under any other circumstances I might not have found myself in circumstances that presented so ripe an opportunity to learn and understand that most sensuous, invigorating, physically challenging and just plain righteous of musical instruments: the guitar.

Would you rather watch TV or play guitar?

Guitarists: Defining the Breeds

The world of the guitar, from what I’ve seen of the various “shows” held here and there, is populated with individuals whom one could classify into three types: There are collectors who couldn’t give a damn about playing but are attracted by aesthetic or monetary value; there are players who’d probably be better off collecting; and there are those who appreciate how truly awful it is to play poorly and therefore practice like hell out of fear that one day they’ll awaken to find they’re a better fit for category two. (For a hint, reread this paragraph.)

I am one of the individuals from the third category. I live to play the guitar, and if it weren’t for the fact that I’m a responsible adult I’d play the guitar night and day. Actually, it’s as much the music as the instrument – maybe more. Put it this way: To play really well, and play like you mean it, you have to dig in to that fretboard. You have to drive the sludge of misguided assumption and fear out of your hands and out of your brain. To do that takes commitment. It isn’t for babies.

Think about it. To play your best means sacrificing those precious hours in front of the flat-screen, where you might otherwise be perfectly happy growing a big TV butt and shrinking your brain while undertalented, overpaid inflata-babes drive up the advertising revenues and your reserves of testosterone. However, to get to the point where you know that what you’re playing is meaningful and clear of hype. To do that, you’ll have to take your treasured six-stringer through neighborhoods you don’t want to live in . . . at least, not permanently.

If you want to play well, practice hard. That’s what I learned early on in my adventure. On the path I’ve taken, there were players with minds to match their hands; people who saved the partying for after the gig, not before it; people who worked and worked and worked and worked at being better musicians, better thinkers and better teachers. I’ve been fortunate to know these people, and I’ve applied those lessons throughout my career as a journalist and musician.

The Twin Horizons

I soon learned that the many possibilities within the timber of the guitar would establish a certain mark upon which I could focus my own musical efforts. That mark became a line that separated what I was capable of from what I wasn’t yet capable of doing, so in that sense the mark was like the horizon itself. For instance, I knew from the first moment I touched a guitar that it was what I wanted, but it was when I found myself in a circle of very expressive players that I knew the instrument would always hold more than my efforts could reveal. That’s what the guitar is, though. It’s a mystery, or a kind of kaleidoscope. The more you turn it and twist it, the more it displays its infinite randomness and potential. And that’s what makes it so damn fun to play. But the more you play, the more the guitar becomes a philosophy. It’s an approach to listening—a way of sensing and feeling—that lets you know it’s okay to strive and fail before you try and succeed. In that way the guitar is one of the world’s great gifts, which is why so many talented artists have told me that their songs and solos seem to appear from out of nowhere. A good friend recently said there’s no such thing as musical genius. Instead, he said, there’s only the act of channeling from a sphere of creativity that’s far too big for one mind to perceive or identify. It made sense to me. Certainly it’d be more fun to pull some incredible theme out of thin air, or maybe out of a dream, than to feel it was some godlike and wholly intentional act: “That’s it, I’ve done it. I’ve just produced another masterpiece, the likes of which the world shall not see a-gain.” There’s way too much pressure in that. It’ll give you acne.

Well, on with the story. You’ll be impressed, I think, because it’s entirely true and free of exaggeration. It might be a bit more intense than what you’ve experienced on your trip, but then it might not be. After all, the story is really more about the experiences than about—well, moi—so the commonalities will reveal themselves as I relate the events. But hopefully those events will help us define a new philosophy, based partly on the old ones but enriched with something newer and less moi-centric. Here goes:

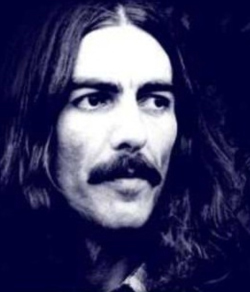

George Harrison's "My Sweet Lord" was all over the radio

It was a long time ago that I began to play the guitar. I was in the eighth grade, and George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” was all over the radio. I’d already learned to play the drums, but since there was little chance that my parents would allow a second set of tubs in the house (the drums belonged to an older brother), I figured my chances would be better with the more compact and more “affordable” guitar. There was one of those in the house too, and it belonged to another brother. I’d been watching him for quite a while, experimenting with his little Orpheus tiger-striped acoustic in the rare dogpoop sunburst. Actually, what I really wanted most was just to pluck those six strings from low to high and follow with a single strum, which was a symbol of the old “Peter Gunn” TV show. Anyway, Guitar Brother eventually relinquished the Orpheus, but rather than deciding I should keep and treasure it the aforementioned two jerks joined with still another brother in destroying it. (Perhaps my oldest brother would have stopped them if he were there. No, he’s classically educated and hates rock ‘n’ roll, so he would’ve helped ‘em.) Hey, but at least it was fun to watch. It also showed me, right at the start of my life as a guitar addict, that there’s always another deal to be had somewhere. So, having owned the Orpheus only a matter of hours and suddenly finding myself without it, I became immersed in the culture of hunter-gatherers. Guitar Bro’ moved up to a Japanese-built Orlando classical, and I got a neighbor’s cast-off Mexican gut-string with the “Missing Tuner Button” feature.

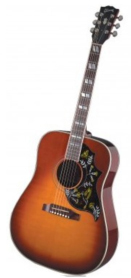

Gibson Hummingbird Acoustic Guitar

One day Guitar Bro’ came home with a replacement for his Orlando, but this one wasn’t about to find itself skewered over a piece of rebar like the Orpheus had. It was a ’63 Gibson Hummingbird in mint–and I mean mint–condition, which had been closeted for eight years by a guy who couldn’t stand the thought of scratching it. (His everyday guitar was a Martin.) From the moment I heard that H-bird, with its thunderous and metallic bass end, woody lower mids and ringing trebles, I knew it would become the sonic standard by which I’d judge every other acoustic guitar. Put it this way: My brother still has it, and I still want it. I want that bitchin’ cherry-sunburst finish, the frets that are wide as skateboard wheels, the fully intact pickguard, the dual-trapezoid inlays, and everything else. Oh, and I’ll take the beat-up Victoria case, with key.

I suffered through a long succession of cheapo guitars, all of them quality-challenged except for the Orlando classical I’d inherited when my brother bought the Gibson. (The Orlando had some truly outrageous Brazilian rosewood. Today, something like that would be a thousand dollars.) But it really didn’t matter to me how bad the instruments were, because I’d practice at least two hours every day, beginning immediately after school. The guitar gave me the power to create chord progressions that reflected the influences of my musical upbringing: the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Stones, Dylan, and the theme from “Bonanza.”

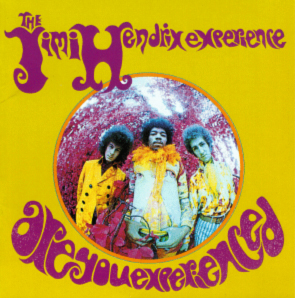

The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Are You Experienced?

Hendrix, Live at Leeds & The Threshold of a Dream

Interestingly, I wasn’t yet hip to the electric guitar when I first heard Are You Experienced blasting out of the hi-fi in a neighbor’s garage down the street. I wasn’t really aware that Jimi was doing all that with a Strat, but sonically it struck me as some of the most powerful and poetic sound I’d ever heard. Over the years I thought about it—becoming a Hendrix freak in the process—and eventually I realized that the instrument and technique are tools that serve the music, not the other way around. In some schools of thought it’s called transparency.

Music was going all the time in my family’s house. And that, I suspect, is where this particular upbringing differed from others. Oh, there was the occasional silence—after all, it wasn’t an insane asylum or a supermarket—but listening to music was a pretty serious pursuit. As much as we gave our time to it, we gave our imagination to it. So, listening wasn’t just a matter of hearing, it was a matter of believing . . . and the music had to be great before we would believe in it. The fundamental distinction is that music wasn’t entertainment in that house, nor was it something we were “allowed” to have “once we’d reached a certain age.” Admittedly we were Anglophiles or even Europhiles, but that’s because there was so much orchestral music to be heard. It was a sensibility that encouraged a real affection for groups like the Moody Blues, as well as later bands like Hatfield and the North. They had everything: melody, harmonic sophistication, musicianship, great production. The haunting improvisations of the Norwegian guitarist Terje Rypdal, and the sonorous melodies of German bassist Eberhard Weber were a revelation too. Listening to their music teaches you that jazz was never strictly an American art form; there’s a classical-based contingent that’s every bit as important.

The Sparkling Storefront

Unshakeable faith can make for a lonely devotion, particularly when you follow something as nebulous and mystifying as music. But as luck would one day have it, a little shop was opening on a commercial street not far away, just down the street from the liquor store. And on the plain stucco edifice over the storefront a guy was spray-painting the image of a cherry-sunburst Les Paul. Wow. I was in high school by this time, and I was totally ready for a place like that. Not that I’d ever held a real Les Paul, but I’d ogled them in the display cases up at the music store in the mall. But I knew this was going to be different. It had to be, because I could clearly sense it. Shoot, I could smell those old guitars and musty little amps from out on the street. And there were two or three guys in the shop, just casually talking and playing. I scooted past the scaffolding and stepped inside.

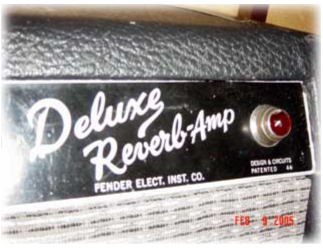

Man, the sound was awesome. I can still see this quiet little gentleman sitting cross-kneed on a stool, cranking big, beautiful blues out of a ’68 Les Paul Custom and a blackface Fender Deluxe. He’d slur, squawk and bend those riffs in a way that was so filthy-dirty and lowdown, I knew I just had to get some of that. The sound was huge and authoritative, but at the same time the man’s approach was perfectly languid. It was one of those moments when you simply have to assume the music comes to you. You prepare, you perfect your tools, and then you lay back and play it. Awesome!

Thankfully, the owners of the vintage shop recognized me as one of their own: a happily addicted adolescent guitar nut who’d do anything to taste that magical concoction of six strings and twenty-odd frets. Maybe they thought I might even buy one of the seven or so ’55 Goldtops that adorned the walls there. Think of that: I was this nice Catholic kid whose every move betrayed a lack of experience in the world, and I was hangin’ out with guys who owned and sold some of the most righteous guitars ever made! I went there nearly every day, and tried not to be an ignorant little punk. That was the hard part.

Other people started hanging out at the shop too, and quickly it became a haven for players from throughout the South Bay. (That’s basically the part of Southern California occupied by Long Beach, which I also learned had an inordinately high number of monster guitarists.) If you were deemed by the owner to be good enough, and careful enough, then you could take the guitars off the hangers and play them. The deal with the shop was this: It wasn’t so much the guitar or the amp as an example of collectible history or an indicator of market value. Instead this was a place in search of the perfect recipe. To that end, everything was considered in excruciatingly precise detail. Fretboards were cleaned and conditioned (with linseed oil, now considered a possible carcinogen), pickups and wiring were inspected, and the amps were taken through a comprehensive auditioning process in two key environments–the carpeted, rough-pine paneled shop, and a crude cinder-block storage room at the back. There were catalogs of tubes and transformers, and there was a constant procession of speakers. These guys would put just about anything in a tube amp: Altec, JBL, Gauss, Jensen, Celestion, Eminence, and eventually some cheap no-name jobs with paper domes and extra-large voice coils. If an amp or guitar had the potential to sound great, the people at the shop could get it there.

Fender was the amp of choice at the shop.

What to Play?

Fender was the amp of choice at the shop. But these were no longer standard-issue Fenders. A local technician who’d developed a relationship with the shop owners had come up with a way to install a “clipper circuit” in place of the tremolo control. A friend told me it effectively electrified the front panel, but I hardly cared. Once I got up the nerve to say, “Mom, I need a blackface Fender Twin Reverb with master volume for my new gig”–and finding that she’d go for it–I was ready for my new moniker: “The Mayor of Solotown.” Sure, I tried the Marshall route eventually, courtesy of a road-weary hundred-watter that had been stripped of its vinyl, together with a similarly raped slant cab whose basket-weave grille was decorated with the residue of beer and barf. I just hated the thing. It sounded so dead – so devoid of ambience. I just couldn’t seem to play the room with it like I could with the open-back stuff. Another member of the inner circle urged me to keep the Marshall, saying it just needed fresh tubes. (Actually, he was right.) Well, a little reverb could’ve helped too! So, I took it back to the shop and got two amps: a silverface Twin circa ’70-’71, and an Ampeg VT-22 of roughly the same vintage. Man, that was nuts. I had way too much power, feedback that was totally controllable per distance and proximity, and the juicy Ampeg “cone-cry” that Marshall designs, good as they might have been, didn’t have. Those two amps worked together almost intuitively, and they made my little ’76 rock-maple Osborne solid-body sing like Pavarotti with his meatballs in a vice. I still think it was one of the most amazing sounds I’ve ever heard.

A benefit of being a familiar face was that I could hang around at the shop and play all these incredible guitars, but honestly the owners didn’t expect me to pony up for something truly vintage. I’d just walk in, and within a few minutes I’d be playing a ’57 three-pickup Custom – a guitar that was so good it could almost play itself. I could pick up a Goldtop with those delicious off-white soapbars and a stoptail, or even the co-owner’s customized Olympic white “studio Strat” with Mighty Mite brass hardware, EMG active pickups and a shimmed Jazzmaster neck, and blow out the licks till my fingernails bled. Over time I bought this guitar and that, like a scarred-up Guild Aristocrat and a fabulous mid-’60s Kazuo Yairi replica of a Martin 0018. And of course they knew I’d buy the ’63 ES-345 that someone had stripped bare with a steak knife and spray-lacquered. But no one ever said, “Hey, why don’t you buy something.” We of the inner circle even helped sell guitars, because we could make them sound like they should. I’d demo guitars for buyers all the time, and if I played it they’d probably buy it.

Once, though, I demoed a guitar for a kid just about my age, and I almost wished I hadn’t. I’d been at home practicing like crazy, and after a while I decided I’d visit the shop. There was this kid there, and he was interested in a particular Les Paul (a white Custom, I think). The manager said to me, “Hey, play something to show what this guitar can do.” So, I sat down and . . . and . . . found that I just couldn’t seem to play for beans. It was as if I was just too tired. Maybe I just felt like a trained monkey. In any case, all the whiplash-inducing improvisational skill I’d developed was singularly absent from my cells, and I just plain stunk on that guitar.

The kid still wanted the Les Paul

The kid still wanted the Les Paul. But once he’d left the shop, I told the manager I felt lousy about having played so poorly. His response was one of the profound surprises of my life up to that point: “So, you’ve been playing too much,” he said. “Now it’s time to just listen for a while.” It was far more wisdom than I deserved, but that’s the kind of friend this guy was capable of being. He was honest, and in his business he was equally so. It was another lesson: Be a listener. Listen to others, listen to your intuition, and listen to the silence that coincides with the noise. There’s a musical comparison too, I think. So much of what passes for kick-ass product these days is exactly that, a product that’s out to prove it can kick your ass. Time was, when there was a give-and-take in even the gnarliest music. There was an ebb and flow, and the tension and release that has characterized so much of the best music.

Our favorite albums

The Immersion Diversion

Clearly I was learning more about playing the guitar than I could have at any music school. It was everything in one package: musical, philosophical, technical, aesthetic, nostalgic and futuristic. There was a massive influx of ideas and tastes running from Delta blues and Africana to British progressive rock, on to German and Dutch hard rock, and tongue-in-cheek quasi-classical stuff from the studios and piazzas of Milan. We believed we should be able to grasp it all, and that we should be able to play it all. But that was part of the era. Perhaps none of us had a master’s degree in music, but there was a constant and intensive exchange of ideas and information. We’d bring in our favorite records by King Crimson, Automatic Man, Soft Machine, Caravan, Golden Earring, Be-Bop Deluxe, The Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Frank Zappa, and even the maniacally virtuoso French ensemble Magma. We’d listen to Taj Mahal, Leon Redbone, Tom Waits, Neil Young, and of course Jeff Beck. The power, the greatness and the grittiness of all that would get mixed together, and there at the confluence of it all we felt that absolutely anything was possible.

The guitars at the shop were generally a cut above, but the one that really had it all was a Flying V dating from about September 1957. It had a honey-colored Korina body so gorgeous, and a neck profile so perfect, that simply holding it was enough to make you forsake any other electric instrument. More than any Les Paul, Strat or Tele, it was the guitar. The tone was monumentally hot—bright, sassy and almost too sensuous for words–and the action over those polished frets and board edges was like something you dream of. And guess what? We used to play that sucker all the time, usually through the shop’s number-one Deluxe with that juicy master-volume setup. Man, it was so effing beautiful! But wait, you’d better steel your nerves for this, because it’ll either make you laugh like an idiot or cry like a baby. Ready? I’ll continue.

Birth of an Angel, and Others

Word had it that our beautiful “V” had been sold to a buyer somewhere down in Texas. But since it was obviously too special to be shipped, his plan was to drive out to the coast and pick it up. We never saw it leave the shop, nor could we have handled seeing it go. But a week or so later the shop manager told us the news. He made the report with an “ouch” of a smile that said all too clearly, “Easy come, easy go.” It turned out that the man who’d purchased the “V” only made it about halfway home with the guitar. He’d been running hard across the Arizona desert in his ’50s Ford pickup when suddenly he caught a whiff of smoke. Something smelled funny, like maybe rubber or wiring. Then he saw the flames licking the edges of the hood up front. Soon there was billowing smoke, fire was everywhere, and just one thing to do: pull over and get the hell out of that truck. He released the door, kicked it open, headed across the blacktop for the opposite shoulder and Kablooey!!! A gigantic pressure wave knocked him on his butt, from which position he could see a mushroom of molten iron and oil roiling toward the blue.

Damn. The Flying V was in the Ford.

It was then that he remembered: The Flying V was in the Ford. He had set it up front with him, leaning it against the bench seat so that he could admire it as he drove along. But as the truck flamed itself to a crisp on that Southwestern highway, the soul of one almighty and godlike guitar silently winged its way to Heaven.

Other axes came and went, and we enjoyed them all. There were baby-blue Strats, Mustangs with racing stripes, Teles and Esquires, a Firebird V that a customer bought and had edge-radiused and refinished wine red, a particularly fine Les Paul Standard with the top refinished in translucent clover honey (like orange juice), and a ’58 blond dotneck 335 that I sincerely wish I’d put on layaway. And if your pickups weren’t up to snuff, good ol’ Bill the shop manager would fix that. He pulled the stock Hi-A units out of my Osborne and replaced them with DiMarzio PAFs that he’d hotrodded with longer magnets. He also installed some pre-amped EMGs and a five-way switch in my Ibanez Challenger II “Buddy Holly” Strat replica. Damn, what a great guitar that was. Wait, there’s something in my eye. Just a minute, the tears will pass.

Excuse me. Once in a while I remember letting that one go.

Robin Trower, Guitarist (Procol Harum)

Fame However Fleeting

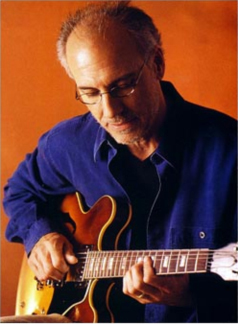

Big-time guitarists would come to the shop, too, usually after hours. For example, it was said that Robin Trower came in one night to audition three ’57 Strats that had been brought in for his consideration. And once I was invited to “drop by” with my guitar when Larry Carlton was scheduled to come in and try a caramel-sunburst ES. I was there for it, just waiting. Eventually he showed up, and after a few minutes he took a seat adjacent to me, on one of those funky squash-colored naugahyde ottomans that every guitar shop ought to have. He just started doing his thing, so I immediately jumped in with mine. It sounded good to me, and I could tell he was diggin’ it, so we played that way for at least half an hour. Eventually I packed up my guitar, but I loitered long enough to listen in as Carlton finished his business with the management of the shop. (He said he liked the ES but that the neck would need some work, which I took to mean reshaping.) Then, when I got home, Bill called from the shop and said, “So, after you left, Carlton goes, ‘Jeez, who was that kid!? He’s great!'” It was nothing, really. When you’ve been living and breathing Wishbone Ash for months, and practicing every waking hour, you aren’t going to feel intimidated by a few Steely Dan riffs.

Larry Carlton, Guitarist & Composer

Life goes on, and eventually I was too busy to visit the vintage shop very often. There was a change in management anyway, so the vibe was noticeably absent. In time I became a full-time writer, covering my favorite subject as an editor and contributor with various magazines. But in all the years since those days, when music focused our minds and fueled our fingers, I have yet to hear more than a handful of guitarists who can touch some of the players I knew from that little vintage guitar shop in Long Beach. I’ve lived in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles and Tokyo, and I’ve met, interviewed and studied with brilliant players. Latin, world music, rock, metal, the studio scene, fusion, and etcetera: all have their names and signatures. But when you find a place where you can immerse yourself in the art of the guitar—where you’re totally free of inhibitions and ready to learn from players of every genre—then there’s no question about it. That’s where you’ll find musicians who are quicker, faster, more fluid, funnier, more powerful, more dedicated, better equipped to improvise and easily equipped to out-rock any of the supposed masters from this or any crop in recent memory. Simply put, it’s the place.

Jeff Beck, Guitarist (The Yardbirds)

The Philosophy Part

What did I learn, and what sort of philosophy emerged from my experiences there? Well, to review them and sum up I’d say it’s as important to attempt as to succeed; that the process is nothing without the quest for the process; that it’s all for nothing but never simply for entertainment; that it’s always worthwhile to want to be the best, even though there is never one “best”; that one should listen to the lessons of accident and random occurrence; that the person that makes the music, though the music fulfills the person; and that if you don’t play as if it were your very last time on this little blue planet, then you’re just wasting your time.

I also learned that you can play almost any kind of guitar you want and sound as good as you want. For instance, I don’t think any of the best players from this particular circle had the money it took to own one of the best guitars in the shop. In fact, I know they didn’t. Those guitars are intentionally priced to remain beyond the reach of the player, so that they’ll neither suffer from player wear nor embarrass the collector who can afford them but can’t actually play. But if you think we ever discussed it or worried about it, you’d be wrong. As I said earlier, we could play the vintage gear nearly anytime we wanted, and it was great. But then we’d head for our own guitars. I had my Osborne, which, if you can imagine, looks like a Rickenbacker 325 with a Mosrite headstock and Gibson-style hardware. Jeff had his lucite Dan Armstrong. Ronnie had a Strat with a fat little Tele neck on it, and Martin had an early issue of the Ibanez Artist in that nice violin finish. With the exception of my Osborne, nearly everything we owned was pre-owned, and certainly everything we played needed some serious tweaking due to overuse.

It’s still a challenge to defend an older guitar against a newer, better-built one. And since I nearly played the Osborne to death—to the point that I’d often fall asleep with it on my chest—I’ve placed it in the deep freeze until I can resurrect it. Instead, I play any of several guitars. For example, I had a superstrat built at ESP Craft House Tokyo in ’85. I hand-picked all the components myself, right down to the slab of northern ash, birds-eye neck and Bill Lawrence pickups. I even had the luthier assemble a Kahler Pro trem with a combination of brass and stainless parts. It has an oiled neck with a lacquered fingerboard, and the body is translucent cranberry. (Don’t ask how I put a belt-buckle dent in the top of the guitar.) Then I have a Yamaha SBG1300TS double-cutaway in gothic black. It weighs more than a Toyota and has a baseball-bat neck, but what resonance! There’s also an early ‘60s Eko model 200 “Mascot” archtop in showroom shape, aged to a delicate apricot blond. It’s small, but like many Eko acoustics it’s loud and very responsive, with tremendous sustain. And I have a four-pickup Eko Cobra that, despite the uprooted frets and shrunken pickguard, still manages to produce a sound that Stevie would’ve swapped his axe for. My current favorite, though, is a beautiful Eastwood Sidejack Deluxe in caramel sunburst. The fretboard is so slick and fast, I just can’t stay away from it. If I were to characterize its sound, I’d say it conjures the tonal balance of a Firebird, or maybe a super-hot Tele. There’s a “long scale” quality about the sound, which I really like.

See? There’s nothing outlandishly expensive. Sure, the Osborne is rare, with a serial number of “0003.” The ESP is tailor-made, and the Eko 200 is a sweetheart Django machine – a total rocket. But I treat each of them as a tool to help reach an artistic goal. It doesn’t take a fabulously expensive guitar to succeed in this respect. Instead you’ll want a guitar that doesn’t hold you back. You can play a guitar that challenges you, but a challenge is distinct from a hindrance. If the pickups are too hot or tend to feed back, you can pull back from “11.” When the intonation is off in the octave register, you can adjust it or deal with it. When there’s a tendency to play one guitar a bit more staccato than you’d like, you can simply relax and play more legato. You can even pick harder, or play fingerstyle, and achieve a similar result. Just make the instrument your own. Teach that guitar how to play and how to sound its best. Then it can teach you in return.

So, if you’re out there, Martin, Ronnie, Rob, Mark, Bill, and especially my old friend Jeffrey, I want to thank you for making me a part of the group. You’ve taught me more than I could ever say, and you’ll always be among my true guitar heroes.

Hello there, I discovered your website by the use of Google whilst searching for a comparable subject, your website came up, it appears to be like good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

beautiful…

The Orpheus Acoustic Sunburst, i found one and don’t know much about guitars, its a little rough around the edges does anyone know what its worth?

Found an Orpheus Tiger stripe Sunburst at Goodwill for 14 bucks. One of the funnest guitars I’ve ever owned. It was missing a fret so I impatiently slapped a finishing nail in the empty space and threw some super slinkys on it. Seriously rich sound for such a tiny guitar.