Last month guitar legend Link Wray passed away at his Copenhagen home at the age of seventy-six. A master of raw tone and minimalist riffs, Link Wray was the great grandfather of the power chord.

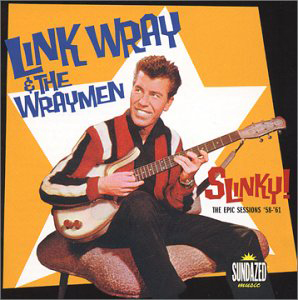

Slinky: Link Wray & the Wraymen

Link learned the guitar at the age of nine from a carnie named Hambone, in town with the Barnum and Bailey Circus. They began their friendship when Hambone noticed Link strumming an old acoustic on his parents’ front porch. As an army brat, Link was used to a nomadic lifestyle. By the age of fifteen he was paying twenty dollars a night to sit in with country-great Tex Ritter, so he could continue to learn his craft.

Lacking the technical know-how of the jazz luminaries of the day, TalFarlow and Django Reinhardt being his favorites, and unable to sing due to the loss of a lung to childhood tuberculosis, Link began to experiment with his sound. He tried such original ideas as poking holes in his amplifier speakers to get a new kind of distortion. Teaming with his brother Doug and first cousin Shorty, The Wraymenwere born. Prestigious venues and Top 20 success followed in 1958, when Rumble (actually titled Oddball by Link) made the Charts.

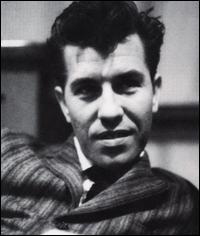

Link Wray

This ushered in the era of the guitar instrumental, and Link stayed ahead of the pack by using unique guitars and the electronics of the day, creating probably one of the first home studios. He called it the Three Track Shack because it was housed in a shed and had only one three-track tape recorder, ;state of the art for the time. By merging chugging blues, surf twang, and psychedelia into a sound that was soulful, irreverent, and individual, Link Wray created a new music. Some people call it Rock and Roll.

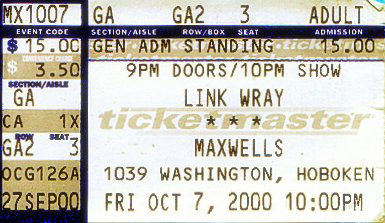

A friend of mine had every Link Wray album. My education began by playing each of these albums over and over. So when Link came to town, it was the show I had been waiting. We plotted and planned, bought tickets and then lost them, bought them again. Two nights later we were ready to go. I slicked up my shoes and slimed up my hair in true Rockabilly fashion, donning a western shirt embossed with tigers. My friend was dressed to dazzle in a late 50s ruby red velvet dress and a pair of knee-high stiletto boots.

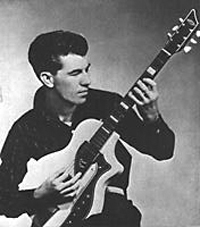

Link Wray with a Supro Dual Tone Guitar

We arrived as Link roared into Rumble. The thrust and the volume of the song was even more powerful live. Link stood firm and anchored the band with ultra-fuzz arpeggio riffs, keeping the trio in tow. With his lanky lumbering frame, a fierce ponytail, and motorcycle jacket, he hunched into his guitar. It was incredible that the man producing this wall of brute sonic strength was in his seventies. As he roared along, I realized that this timeless music has never been more alive. After Jack the Ripper, Rawhide, and Ace of Spades (some were played twice during the evening), he launched into one of his more way-out songs. He cranked it all the way up and I realized this was probably the last song of the night.

Link Wray concert ticket (October 2000)

My friend and I rushed forward to witness the rollicking rave-up. We slid in next to the stage, and with a wail of his guitar he seemed to play off of us alone, looking our way with an expression of childlike wonder. I figured he had his eye on my lady friend. Then something remarkable occurred. He walked over to face me, continuing to play. As the eyes of a shaman stared into mine, he strummed with his right hand and motioned for me to play the neck. And there I was, dear reader, simultaneously reaping the riffage with the legend himself. As tom toms rolled and cymbals crashed and the electric bass pounded to a climax, Link looked directly at me and nodded as though we had shared an intimate secret. In the next moment he was center stage again, commanding the final surge of power and sound to ecstatic applause. My friend also reveled in the moment, a firsthand witness to a dream come true.

Link Wray on stage

All the greats have come across Link at one point in their musical development. He didn’t live to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but was inducted into its Rockabilly counterpart. Bob Dylan, hearing of Link’s death, covered Rumble last week. Neil Young once said, if he could see any band in the world, he would chose Link Wray and The Wraymen. Simply put, the king is gone, but he is not forgotten.

Post by: Devin Patrick

I worked with Link, his Brother Vernon and his bother in-law Rick Cole(?) in Tucson Arz. in the early 70’s. While I worked at a recording studio there, Copper State Recoding. I am not a musician, but loved what Link could do with his guitars. I even talked him into letting put the electronics for his fuzz box in the body of one of his guitars. He had names for them that I don’t remember now but I think it was red. Even went with them to LA to do a tour but from what I was told Polydor Records wanted Link to sign his life away for the tour to go on. So Link told them where to put it. I went back to Tucson and mixed an album for his brother Vernon before moving on. Those were the days…….

Hey William,

Do you remember what fuzz pedal you installed in the guitar? I really loved his early seventies clean to fuzz. The fuzz and tremolo arm work is so sweet!

Thanks ,

Rick P

Hey bill, rick cole here

he called his guitar Screaming Red

if you ever heard it you’d know why

the tour died because the record company went with Golden Earing instead of us.

too bad, the Who were the headliners

I love guitar and I am learning it now. Link Wray one of my idol. whenever i saw something related to him i just read it. i love that post.

Check out this pbs doc coming out soon ..:.

RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World brings to light a profound and missing chapter in the history of American music: the Indigenous influence. Featuring music icons Charley Patton, Mildred Bailey, Link Wray, Jimi Hendrix, Jesse Ed Davis, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Robbie Robertson, Randy Castillo, and Taboo, RUMBLE shows how these pioneering Native musicians helped shape the soundtracks of our lives. This event is open to the public. FREE admission to the Museum beginning at 4:00 pm. FREE screening of RUMBLE begins at 6:30 pm. For more information or to make your FREE reservation go to RSVP@gpb.org/community