The question is ridiculously simple, but players throughout modern musical history have found it nearly impossible to answer: What kind of guitarist are you? If we’re not asking ourselves this kind of thing, we’re expecting others to answer it for us. Apparently, for a guitarist it’s best to have an affiliation. If you’re a jazzer or a blueser, then you’re no longer a danger to yourself and others. It’s an easy affiliation, like voting for a candidate simply because you think he’ll win. It’s like carrying a bigger club because you think it’ll make you a better caveman. And think about what it does for your image! If another jazzer should happen to hear you slide into a chord or play a staccato run behind the beat, then you must be all right. Or, if you make those notes plink and sting even with the tone rolled back to five, then you’ve got the stuff for blues. Just don’t rock too much, because then you’ll be pegged like a zit-faced kid at your big sister’s cotillion.

Not everyone is so easily fooled by the argument that one form or style of music is better or more valid than another. There really are guitarists who can walk either street, reflecting the mood with appropriate ease and authority. But since they realize it’s no use distancing one path from the other, they just allow the two routes to mingle and intersect, creating a style that’s more relevant to the music and the moment.

The truth is, playing it all requires a measure of self-assuredness. Call it arrogance, or call it balls. But if you can rip off those three-octave runs, play the big chords and take it to Chicago in one go, then you’re too cool for school. You’re ready to get out there and do it.

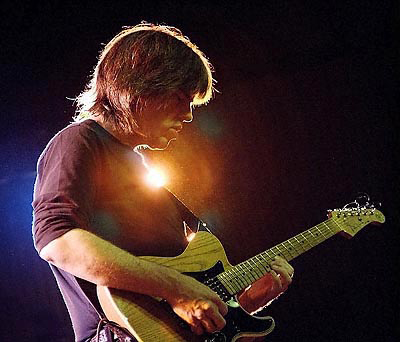

Jazz Guitarist Mike Stern

The Man with the Axe

Mike Stern is one of those lucky few: a guitarist who can do it all. Though he’s known for the depth and precision of his jazzy ballads and rip-snortin’ fusion instrumentals, he’s equally respected for the woozy bends and woody tone of his paeans to the greats of blues and rock. Listen to any of his many excellent releases (all of which remain active in the Atlantic catalog), and you’ll caught by the power of his deceivingly subtle blend. He’ll start off a solo slowly, with notes that rise and fall like the undulations of a woman in the throes of romance. Those few moaning notes soon take on the tone of spoken utterances, urging the action. The speed builds, the intervals become more dramatic. The whole thing rises to a crescendo of volcanic proportions, climbing to the very pinnacles of stately, guitaristic glory. (Sounds like sex, doesn’t it?)

It’s really remarkable that Stern can sustain those levels of excitement over the course of solos that are much longer than is typical of either the jazz genre or rock. After all, these aren’t cheap little power ballads, they’re full-blown hotrods of composition and jazz improvisation. That’s right, they’re long and they’re loud. It’s convenient to compare Stern’s manner of opening to the sound of the late blues master Roy Buchanan (whose ancient Telecaster he would one day own), and rock archetype Jeff Beck. But those guitarists, despite their brilliance, didn’t leap the song format and compose for entire groups of musicians. Mike Stern has.

Early exposure to many kinds of music gave Stern a head start in his ability perceive the melody, or the long line, at the heart of a piece. His mother was a big influence there, being a fan of the great composers and jazz artists alike. Their home in D.C. was always alight with sound. As he says, “My mom used to play a lot of classical records around the house. I got into that, along with a lot of jazz. But I still listened to the Beatles, the Stones, Jeff Beck and Hendrix.” Which makes complete sense, since the Beatles, Hendrix and the best of their day couldn’t have done what they did without considerable background as listeners.

Early Explorations

Mike was born in January 1953, into a family based in the Boston area. Later on they moved to Washington, D.C., where, at his mom’s insistence, he took up the piano. By the age of 12, however, he’d made a decision about what he should play. And it wasn’t going to be the piano. Soon came the fateful six-string, an unassuming plywood job with nylon strings. “I took a few lessons,” he says, “but after a while I started playing by ear. I did that for a long time, and it just felt right. So, now it’s whatever gets to my heart. It could be simple, or whatever. In those days it was simple by necessity, because I didn’t have very much knowledge. Later I began studying more, because I wanted to grow and improve my understanding. I dug jazz, but I’d learned to play rock and blues by listening to records. Still, when I took my mom’s jazz records into my room and tried to play along with that stuff, I’d get lost right away. To be honest, I felt like I was in a rut playing only rock and blues.”

Mike Stern with Band Mike enrolled at the Berklee College of Music in 1971, just a few blocks from Fenway Park and the legendary Red Sox, and began a more in-depth exploration of jazz. That was where he finally got serious about it, thanks to the encouragement of guitar instructors such as Mick Goodrick and a very young Pat Methany, who had also been a student of Goodrick. Along the way he developed a deep respect for jazz guitar, notably the innovation of Wes Montgomery and the delicate touch of Jim Hall. Goodrick, however, was known to use an approach that was esoteric, in that he’d focus not on the instrument but on the individual.

Goodrick’s way of saying it was, “You are who you are first, and your music is secondary. Your playing reflects that relationship, so in turn you have to represent what your vibe is.” It was his way of saying the player comes first. Really, though, the music itself tends to do that. When the music is real, it comes through in a positive way, and that’s really powerful. People put their energy into something that at the very worst is harmless and at the very best is incredibly great. I think we need a lot more of that kind of thing.”

Goin’ Home

Stern eventually began to feel he should leave the academic environment of Berklee and return to D.C. So, home he went, and before long he was playing rock and blues gigs throughout the region. “I’d studied with Pat Methany for about a year, before I went home. Eventually I went back to Berklee, and Pat told me then: ‘School is great, but you gotta get out and play.’”

It was the message Mike needed to hear. He decided that he’d have to work harder than ever to make something happen, and by 1976 he was ready for the next step up the ladder. Word got out that the long-established band Blood Sweat & Tears was looking for a guitarist, and Stern was among the many who took the test. “There were all kinds of cats auditioning for that band, but [drummer] Bobby Colomby gave me the call. I auditioned just for the sake of doing it, and I got the gig. Man, if you can get that kind of experience, it will do so much!”

The spot in BS&T proved to be a lucky one, even though the band was well past its days as a hit machine. Still, BS&T was never a band that suffered fools lightly, and Mike knew he was working in the company of some seriously talented players. Among them was Jaco Pastorius, a former drummer who had quickly made a name for himself as the self-proclaimed king of the electric bass. The two quickly struck up a friendship, and since then Jaco’s unmistakable mastery of the fretless Precision bass has remained an inspiration for Stern.

New York: The Core Issue

Things change within and without, so Mike knew that Boston couldn’t be his home base forever. Besides, now that he was gigging with career performers and studio veterans, he wasn’t going to be sitting around the house much. So, once his career was off the ground he made the move to New York. He got used to the pace of it easily enough, and soon he and his girlfriend Leni (whom he eventually married) were offered a loft above his favorite jazz haunt, 55 Grand St. They just couldn’t say no to that. Imagine you’re actually living at the hippest little spot in town, and that you can actually gig right there. You’d be tempted to think there was actually a choice between brushing your teeth and plugging in your guitar. It made for an interesting lifestyle, and Mike became known as the guy who lived where he worked . . . in a manner of speaking.

Typically, Stern is humble about the way he’d become so much a part of that elite circle. It’s not about him, it’s about his friends and the memories and experiences they provided. “Jaco used to hang out a lot,” Mike says. “He’d always nudge me along. He and Pat seemed to have a lot more faith in my playing than I did. So, that was an interesting period. As time passed I was able to play a lot better, and I used to jam with Jaco all the time. He’d come up to New York, and we’d just play and play. So, it turned out that I frequently got to jam with people who were way better than I was, which helped me get my shit together.”

The guitar is always a big part of Stern’s life, but his discipline with the instrument has resulted from the combined influence of a busy circuit, a cadre of talented musicians, and the drive to acquire knowledge. “No matter what I’m doing,” says Mike, “I try to get a little place lined up where I can play. For example, I was playing with Bill Evans, the saxophonist, at a place called “Michael’s,” which is closed now. And Bill told me he’d be hitting the road with Miles. But I was also playing with Billy Cobham at the Bottom Line, there in Manhattan, so Evans brought Miles down. Eventually I got the call to do that gig. In fact, the title for “Fat Time” [from Davis’ classic The Man with the Horn] was taken from the nickname they gave me.”

Stern made his stage debut with Miles at the Kix club in Boston in June of ’81. That performance would see release as We Want Miles, the second of his three records with the band. This leg of the gig lasted for two years, producing a series of recordings that would get the jazz and rock communities buzzing with news of a guy with fret-melting prowess on the guitar. Three of the era’s most powerful sets—The Man with the Horn, We Want Miles, Miles! Miles! Miles! (Live in Japan) and Star People—showcased the journeyman guitarist. His sound blended the primal energy and sensual textures of his long-time hero Jimi Hendrix with the harmonic breadth of Wes Montgomery. “Fat Time” remains an awe-inspiring example of the monumental structures that Stern can create with a solid-body axe and a touch of chorus.

Jazz Guitarist Mike Stern

A Sense of Self

Jaco’s influence up to this point had been positive in many ways, but of course there was also a negative aspect to it. Despite the benefits of being able to play together whenever they liked, the pair had taken the party route a bit too often. Excessive alcohol consumption had begun to wear on the guitarist, depleting his energies and stressing his home life. So, after a while it was clear that he needed to chill out. Fortunately the job with Miles was still open to him, so Mike returned for another year’s work with the maestro. Then, around the next corner he found work with Steps Ahead, the progress and highly respected ensemble featuring vibraphone virtuoso Mike Mainieri. That led to a spot in a Brecker Brothers’ quintet, which would again mean a lot more experience.

The years following were busy ones for Mike, and right through 1986 he worked with one headlining act after another. Still, there was a need to see what he could do on his own terms. It was an insistent (some might say innocent or even dangerous) curiosity about life outside the bubble. It was 1986, and with his second stay in the Miles Davis unit drawing to a close he’d managed to put together a band with saxophonist Bob Berg (now deceased) for the recording of his first solo LP, Upside Downside. The record made its debut on Atlantic Records, marking the start of a ten-disc tenure that would create a spot for Stern among the leaders of modern jazz guitar. Upside was the record that made it possible for him to make music under his own name, entirely on his own terms. That was pivotal in Stern’s career not just because it followed on the heels of the Miles Davis records, but because it was the guitarist’s signature as a writer and musician. Cuts like “After You,” “Little Shoes” and the title tune were proof of his ability to create music that could stand on the basis of its solid, song-like structure and cohesive melodies. To put it in other words, Mike Stern made music that was intriguingly elaborate but totally memorable. The icing on the cake was a set of solos that just totally f***ing burned. (The writer remembers asking a friend and session guitarist in L.A. if he’d heard Upside, and his immediate response was, “Jeez, could ya get any more intense!?” That’s the effect this record had on even the most astute players.)

The critical success and very respectable sales of Upside Downside were encouraging for Stern and the powers-that-be at Atlantic. And because he knew from the start that doing a solo record was the right move from a personal standpoint, he’d also earned the freedom to compose music that suited his own rules (or lack of them) as a modern electric guitarist. What followed Upside Downside was the ’88 disc Time in Place, which offered a similar blend of bop-inspired rockers and emotive ballads, but with a slightly more “mature” sound thanks to the contributions of players like drummer Peter Erskine, keyboardist Jim Beard and organist Don Grolnick. The next year, though, Stern lit it up again on Jigsaw, with the New York-based guitarist Steve Khan as producer.

What Stern succeeded in doing, over the next several albums as the leader and soloist in various formats, was to make an otherwise technocentric genre work on his terms. And those terms would include a range of music and themes from an increasingly colorful palette, covering everything from standards to hard bop to music of a more global perspective. There was simply no way to lock him in or tie him down. If you liked what Mike Stern did, you’d go wherever the trip took you.

Labels Are for Cans

Stern’s previous works emphasize the textures that multiple instruments create when they collide and intertwine—like the two parallel roads that in some miraculous way intersect. But the recent CD Voices again resists the temptation to stick with the tried and true. Instead it combines Mike’s guitar with the ensemble voices of singer/bassist Richard Bona, Philip Hamilton, Elizabeth Kontomanou and the singer/percussionist Arto Tuncboyaciyan (whose talents have helped make Al Di Meola’s World Sinfonia projects so provocative). This is occasionally called “vocalese,” which is an attractive way of saying “singing without words.” But if you’re tempted to assume it’s more of that generic “marina music” for happy times and empty heads, forget it. One listen to the somber “Still There” or the gut-wrenchingly real “What Might Have Been,” and you’ll understand why some people wear sunglasses around the clock.

Major-label music is very strictly packaged today, of course, and the industry’s lawyers and dealmakers have a disproportionate say in the process of planning and marketing a project. It’s a circumstance that has polarized the industry, on one hand feeding the wealth of puppet entertainers while cutting off the opportunities for musicians who should be just as deserving. One can’t deny that in a world where real music can be seen as odd, and where very few people would bother to invent music if it didn’t already exist—the general population needs to be told what kind of music is preferable or valid. Like the guitarist who feels the need to “be” a bluesman or a jazzer, the casual listener can feel put off or even insulted by music that’s beyond his experience. The industry simply attempts to eliminate the problem. Quality has nothing to do with it.

So, in a way it’s amazing that we can still buy music that’s made by people like Mike Stern. He simply does what he does, when he wants and with the musicians he wants. For those of us who bust our butts to play our best, it’s an important message: The idea isn’t to be different but to be true to oneself, and in so doing be different.

“I never have anybody to answer to,” he says. “So far, I’ve been very free to do just what I’ve wanted. That’s one thing: I feel as if there’s been plenty of effort to make sure I have that creative flexibility. At some point I’d even love to write for more instruments, and for different kinds of instruments. I have a pretty good idea of what I want from people in the group context.”

Mike Stern’s career as a guitarist mirrors the quest that so many of us face as dedicated players. For many it’s a quandary, given the options and the indefinable nature of the art. Here’s the guy who loved blues and rock so much that he nearly played the life out of the stuff, but who ultimately found himself at a critical intersection. He didn’t turn back or come to a screeching halt. He just kept going.

Great in-depth writing on a career that has been crafted with influences of the best musicians alive (and deceased). Congrats. This was a sweet read.