There you have it: Music IS Mathematics. Awful as it sounds, it’s the truth. But don’t let it scare you off. The highest number I’ve ever heard in the context of music is 13, so you don’t have to be a genius to figure it out.

Music is Mathematics

There are two basic numbering systems in music. One has to do with the scale, the other with the key.

Let’s look at the numbers relating to the scale first.

There are seven notes in the scale. Simple enough. The order of intervals, or spaces, between these 7 notes is what makes it unique. The formula, as we should all know by now is Tone, Tone, semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, semitone.

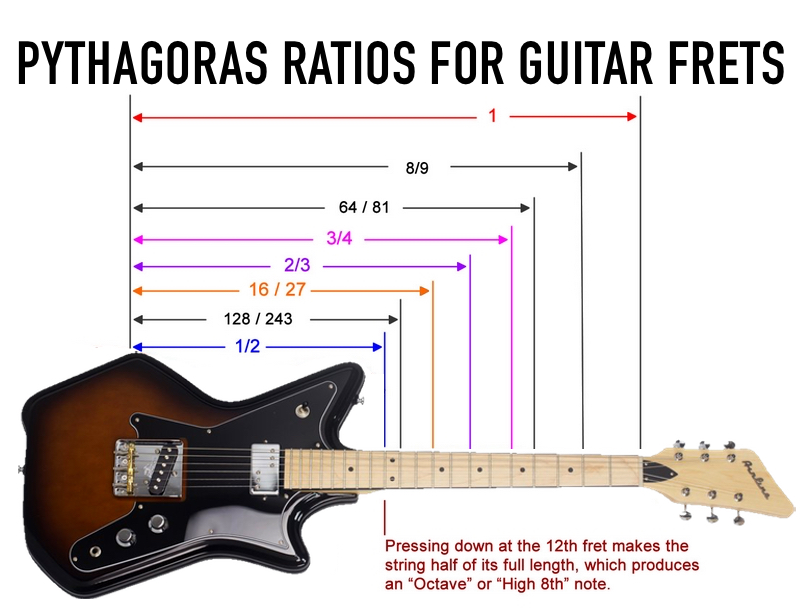

Pythagoras ratios for guitar

Understanding the notes

So our first little bit of math is to understand that from the TWELVE notes of the chromatic scale — all the notes — the scale uses SEVEN, spaced out as described. If there were six notes in the scale, you could imagine them evenly spaced a tone away from each other. But there are seven, so there have to be a couple of semitones thrown in.

(These seven notes by the way, weren’t simply chosen by someone long ago to be the ones we’d all use. They also come from mathematics, from fractions. For example, a vibrating string tuned to A440, when halved will produce another A note, but vibrating at 880 cycles / second, an octave up. That same string doubled in length will vibrate at 220 cycle / second, yet another A an octave down. That same string cut in 3 will produce E notes, and if you cut it into quarters and make 3/4 of it ring, you’ll be listening to a D note. Try it out on your guitar, you’ll hear for yourself. By the way, the halfway mark of guitar strings is the twelfth fret, the one third mark is the seventh fret, the one quarter mark is at the fifth fret.)

Back to the seven scale notes. Chords are made by combining alternate notes from the scale. The simplest chord of all is the triad. It uses three alternate scale notes. The old one-three-five.

You can add other scale notes to those to make an extended chord. The next alternate note is the seven. So a One-Three-Five-Seven combination is called a major seventh.

Mathematics Quote from Oswald Veblen (1924)

You can add a ‘Two’ note to the chord, but it has be added on the treble side of the grouping, so you’re actually using the ‘Two’ from the next octave up. Since the root (One) note of that octave can be seen as the eighth note of the scale, a ‘Two’ note is the next one up, the ‘Nine’.

You can use the ‘Four’ note if you want, but since it’s only one semitone away from the ‘Three’, it actually replaces the ‘Three’. This chord is called ‘Sus Four’. It begs to be brought back to the Three.

If you add not the Seven note that is in the scale but the next note down, the ‘minor Seven’ it’s sometimes called, you wind up with a Seventh chord, as distinct from the major seventh. They’re also referred to as ‘dominant’.

‘Elevens’ are ‘Fours’, ‘Thirteens’ are ‘Sixes’. (Simply subtract seven from those big numbers to find out which note is being called for). And so on and so. It’s pretty straight forward really: the numbers refer to the the seven notes by their order. Just remember that the One-Three-Five are taken for granted as being present.

The next set of numbers refers to the chords within the key. Each of the seven scale notes qualifies as a starting note to build a chord using the alternate note rule. These chords are often written as Roman numerals.

I — II — III — IV — V — VI — VII

Sometimes, you’ll see them written like this:

I — ii — iii — IV — V — vi — vii

This is a good way of doing it because it shows the major / minor quality of the chords. As I’ve been trying to impress upon you, it’s really important to instantly know what all those chords are for any key. Remember The Music Building I wrote about recently.

Let’s say you see a chord written as V7. What does that mean? It means it’s the Five chord from whatever key you’re in, and it’s the Dominant Seventh version. So if you’re in C, you’re looking at a G7. Or a vi7? That would be Am7.

Record producers often write tunes out simply using the numbers. If they’re unsure of the singer’s range, they will choose a suitable the key in the studio. Only then will the numbers become actual chords, mentally converted by the players. Nashville is famous for this kind of notation.

Of course, time signatures and tempo are also related to mathematics. In fact the method we use to crank up a song is for someone to yell out ONE – TWO, A ONE – TWO – THREE – FOUR. The whole of music is one seething mass of numbers when it comes down to it. Lucky for us it sounds and feels so good to make listen back to, otherwise who would bother trying to figure it out?

I hope this article hasn’t put anyone off. The fact is, all these numbers simply become music when you do put a bit of effort into practising it. The layers of music become distinct and workable. Then the fun begins…

Kirk Lorange is one of Australia’s best know slide guitarists. He is also the author of PlaneTalk guitar method. Check out his sites: www.KirkLorange.com and www.ThatllTeachYou.com

Good info here, would like it expanded even farther. Where could I get more on this?

JCLEE:

By far the best resource for learning (useful) music theory, and not wallowing in useless scale-excercises (in 99% of the theory-books out there), would be Carolkaye.com. Not trying to be overly dismissive of the prevailing way of learning, but I tried both ways, and Carol’s chordal methods are FAR more effective towards becoming a good musician, than learning scale-notes/excercises. This is from my personal experience as a player and a teacher. Up until around the late 60’s, this was the way everybody learned music structure/theory. Chordal-learning is also a lot more fun…

Hope this helps!

Good luck!

it is interesting