I’m writing this from Twentynine Palms, CA, where a few years back, my wife Gayle and I bought a cabin to getaway (very away) from it all. We spend our days hiking Joshua Tree National Park, walking and driving around to and visiting the hundreds of abandoned homesteader shacks, playing guitar and singing on the porch, writing, reading and doing as much of nothing as possible. It’s a great place—still, at the relative turn of this new century, something of a well-kept secret.

People come out to Joshua Tree for many reasons, but the major ones are: to go to the national park, to be in the presence of so much beauty and peace and quiet, to spot UFO’s at Giant Rock, to scout the best location for their new meth lab (the city’s a better bet, for you Junior Achieving Speed freaks out there), and to do what we do in the staggering heat of our porch: Nothing much.

And people stay at the Joshua Tree Inn, about 14 miles west of our place, for all these reasons, plus one very specific one: to stay in Room #8.

Gram Parsons: His life came to an early end at the Joshua Tree Inn

Because as many know (evidenced by the frequent waiting list for the room), Room #8 is where, on September 19, 1973, Gram Parsons, relaxing after having finished his second solo album, the classic, although laden with too many slow as molasses tunes, “Grievous Angel”, died. He was a amazing singer—listening to Gram Parsons’ cracked beauty of a voice dance over a 7th chord is one of the most painfully gorgeous sounds that has ever been captured on recording equipment. There were singers with better chops, to be sure. Though, as my friend John points out, Doc Severenson had better chops than Miles Davis, who couldn’t play in the upper register. Chops are never the whole story when you’re talking about art.

The thing Gram Parsons had is what all great artists have—he wasn’t cool or ironic. He was willing to stand, metaphorically naked and striped bare to the essential emotions. And, he could sing like no one else before or since. As someone once said about Keith Richards…everybody switches from C to F, but nobody does it quite like Keith Richards. And nobody sounds like quite like Gram Parsons.

Gram Parsons died when he was 26. We are past the 30th anniversary of his death, which means people have been missing Gram Parsons from this Earth longer than he was on it.

The circumstances surrounding his death and burial have been told and retold (most recently mistold in the so-so indie film “Grand Theft Parsons”), but I’ll offer them here in a brief summary to those who don’t know it. Skip ahead, if you do.

Gram Parsons’ stepfather, by most accounts an oily and brutally self-interested man, tried to rush GP’s body to New Orleans for burial. There was some Louisiana loophole that would allow for Bob Parsons to claim Gram was a New Orleans resident and thereby get his hands on the rather lucrative Parsons’ estate.

Phil Kaufman, a friend/hanger-on/road manager to Parsons and, among others, the Rolling Stones stole the body, with help from friend Michael Martin, from LAX, where it was waiting to be shipped to Louisiana. The reasoning was simple: Parsons had told Phil Kaufman, earlier that year at Clarence White’s funeral, that he wanted to be cremated in his beloved Joshua Tree, where he had spent so much time.

Kaufman and Martin then, in an alcohol and drug-induced haze, drove Parsons to somewhere around his beloved Cap Rock in Joshua Tree National Park (then known as the Joshua Tree National Monument in its pre-national park days), poured gas over the coffin and lit it on fire. They high-tailed it out when Kaufman (mistakenly, it turned out) saw park rangers chasing them. The half-charred coffin was discovered the next morning by hikers (and reported as a “big burned log”), and the remains of the remains were then shipped to New Orleans, where a dying Bob Parsons claimed and buried them.

And now, every year, people come to stay in room number 8, where the sad and brilliant life of Gram Parsons came to such an early end. The question is: Why?

There’s maybe the easy reason of people being obsessed with celebrity. But that misses the boat on a couple of scores. One is that Gram Parsons wasn’t that famous, or that much of a celebrity (at least not when he was alive). He was a great singer/musician, but he wasn’t that popular in his lifetime. For instance, Jim Croce was scads more popular, and he died the same week as GP, and yet no one goes to whatever small airstrip it was that Croce died over. There is no pilgrimage to the flat where Jimi Hendrix died (of course, not many people die in a Bed and Breakfast, as GP did, where it’s kind of convenient to pay your respects).

People are macabre, make no mistake. Henry Ford, reportedly, had the last breath of Thomas Edison sealed in a jar (which lead to all sorts of gruesome deathbed breath-collecting images), so there may be the ghoulish desire to capitalize in whatever personal way on someone’s death. It’s a tenuous analogy, the Ford/Edison thing, and the staying in Room # 8, I realize, but maybe it’s a way of claiming the dead as our own when we have these personal rituals after they’ve left.

But, I’m thinking it’s not for such seedy reasons that people come and stay in Room # 8 and walk around Cap Rock, where Gram Parsons’ ashes are said to have been scattered. And sing sad GP songs on their porch in Twentynine Palms like Gayle and I do all the time. I’m thinking, maybe, there’s a sincerity of purpose at work here.

There’s an old African (I think…I’m a musician, not a scholar) folk tail a friend told me one time about a squirrel and a lion. The lion, after a relatively short chase, had caught the squirrel in its mouth. The squirrel said, “I know you’re going to kill me, but would you let me down for just a second beforehand?” The lion did. The squirrel thrashed around in the sand, and then said, “ok.” The lion asked what that was all about. The squirrel said, “I know you’re going to kill me, but at least now, people will come by here and see my marks and know that I struggled.”

Gram Parsons had, by most accounts, a tough life with many demons. Which doesn’t make him unique. But Gram Parsons, whatever else he did or didn’t do, left some of the most beautiful signs of all of our futile struggles in the sand. And maybe that seems to matter somehow, listening quietly to your own breath inside Room # 8, while the high desert winds swirl outside, much like they probably did on the night of September 19, 1973.

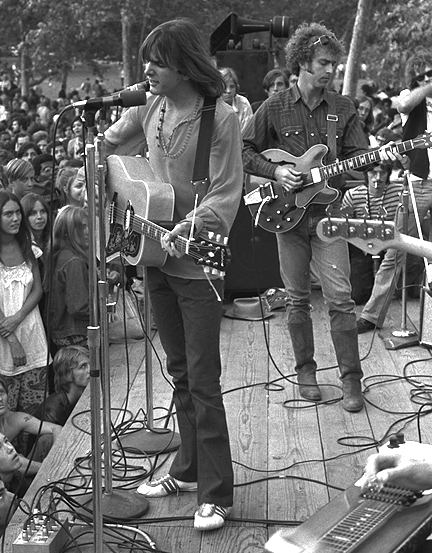

Thanks for this great article. Can I also ask where this picture came from? I’ve not seen this before. . ?

Thanks so much, Michael. I’m sorry to say I don’t know this photo’s source. I think the folks at myrareguitars found it. I think it’s the later (second album) version of the Burritos, as Bernie’s on guitar and Hillman’s back on bass. So, it’s near the end of the band, I’m pretty sure. But I don’t know the source. Apologies.