After a long days work it’s nice to have a peaceful, yet quick drive home to set into relaxation mode. Although, when fortune smiles against you and the drive is filled with red lights, it’s easy to get frustrated. Even more aggravating would be having to sit next to some guy with his speakers full blast at every single light…

Maybe if you could actually make out the song they’re listening to it might be enjoyable… But instead all you get is the “thud thud thud” from the bass! Why is that, anyway?

It’s all about vibrations, and transference of energy. The speaker receives a signal to start vibrating, which starts a ripple effect causing nearby air particles to also vibrate. If a solid object is in the way, this energy will react in a way dependent upon:

1) the material and size of the object, and

2) the frequency and amplitude of the sound.

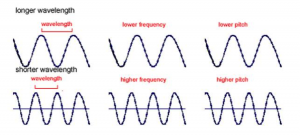

The lower the frequency, the larger the sound wave produced. Bigger sound waves have an easier time resonating with larger objects, while higher pitched small waves will bounce off. If your neighbor rolled down their car window, the smaller waves would have an easy escape and you’d actually be able to hear the song.

Different instruments initiate these vibrations in different ways. For example, on a recorder, in order to play the lowest note possible you need to close all the holes before blowing into it. This creates the largest air cavity it’s capable of, therefore creating the largest sound wave and the lowest note.

Have you ever looked inside a piano? You’ll notice that the longest, thickest strings are the ones responsible for making the lowest notes.

A guitar operates in a similar way – the difference being that instead of hitting a thicker, longer string to produce lower notes, you physically change the length of your strings to do so.

The three main things that tell a string what note it’s going to play are its length, tension, and size. On a guitar, your strings are all the same length between the nut and the saddle. In fact, each string is under a similar amount of tension as well (somewhere between 15 and 20 pounds of tension per string). The reason each open string produces a different note therefore, given the same length and similar tension, has to do with the size of the string. A thicker string under the same amount of tension as a much thinner one will create a much lower note. For example, if you wanted to tune the Low E string to sound like the high B, you would end up tightening it to the point that it would just snap. On the other hand, If you tried to tune the High B so it sounded like the Low E, the string wouldn’t have enough tension to properly vibrate. The sizes of the strings on your guitar were carefully calculated by their manufacturer to achieve a proper balance.

Of course – your guitar has more than six notes! When you start playing and fretting notes, you are essentially decreasing the length of each string. Lets say you play an E in the seventh fret of the A string. The distance between fret seven and the nut no longer has anything to do with the note that string is producing – it is now dependent on the shorter distance between fret seven and the bridge. The string hasn’t changed it’s size, you’ve just shortened its length, thus raising its pitch.

So what if your guitar is out of tune? If a string is flat or sharp in the open position, you can increase or decrease its tension by simply turning the machine head to bring it to pitch. However, what if it already is in tune, but when you fret a note it’s sharp or flat? This is when you’ll need to intonate the guitar by slightly adjusting the strings’ length.

Before you intonate your guitar, you’ll want to make sure your neck relief (talked about in my previous article) and your string height (will talk about in my next article) are already set the way you want. If your action is too high, you have to push the string further towards the neck in order to sound a note. By doing this you’re essentially bending the string, potentially making the note too sharp and giving you a poor reading.

Once your action is set, you can test the intonation. The distance of the strings from the nut to the 12th fret should be equal to that of the 12th fret to the bridge. If the bridge is placed in the wrong spot on the guitar, automatically you know you’ve got a problem! If it’s in the right spot, then you should just need a few minor tweaks to get the guitar intonated. For this example I’ll be using an Airline 2P with tune-o-matic bridge.

First, play the open A string. Make sure it’s perfectly in tune. Then, play the same A string one octave higher in the twelfth fret. If the tuner reads that the note in the 12th fret is flat, you will need to shorten the string between the 12th fret and the bridge by moving the saddle closer to it. If it’s sharp, lengthen the string by moving the saddle away. Repeat this process until each string reads the same note when played open as when played in the 12th fret. That’s it! Well… hopefully. Other factors can come into play like worn frets, twisted necks, or even applying too much pressure to the string. These are all things that you will, of course, want to fix to have your guitar play in tune all the way up and down the neck.

Happy playing!